ISSUE1689

- Mark Abramowicz, M.D., President has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

- Jean-Marie Pflomm, Pharm.D., Editor in Chief has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

- Brinda M. Shah, Pharm.D., Consulting Editor has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

- Discuss the 2023-2024 recommendations for antiviral treatment and prophylaxis of influenza.

- Compare the antiviral drugs available for treatment of influenza based on their efficacy, dosage and administration, and potential adverse effects.

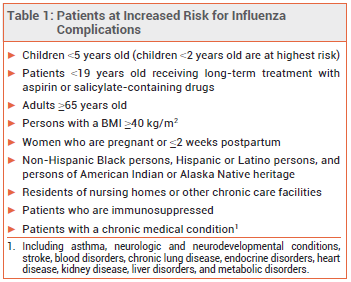

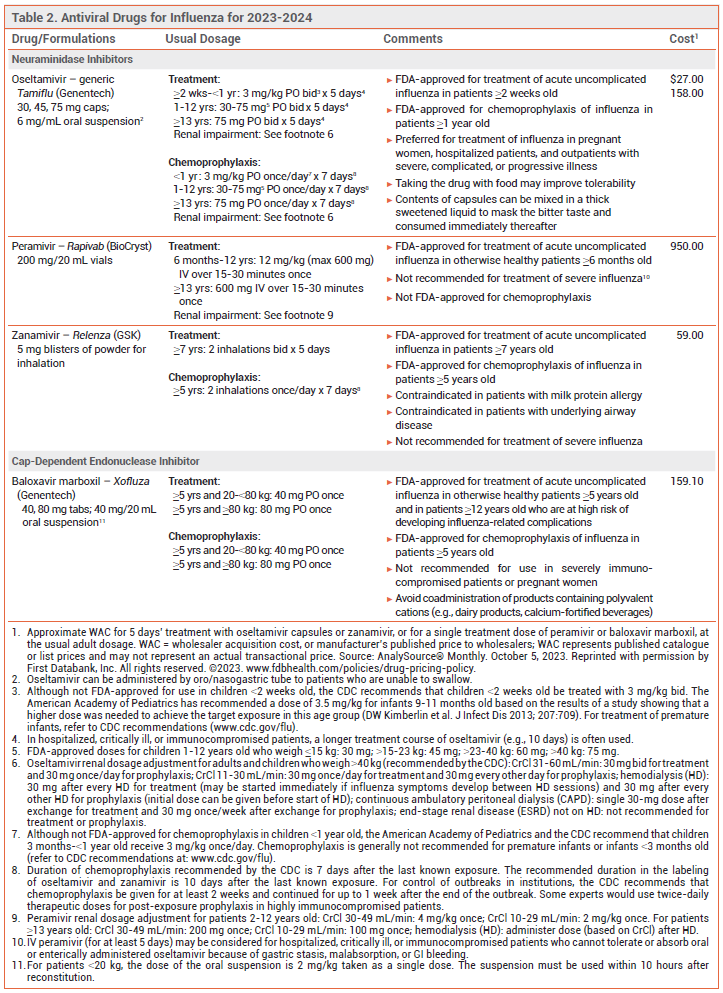

Influenza is generally a self-limited illness, but pneumonia, respiratory failure, and death can occur, especially in patients at increased risk for influenza complications (see Table 1). Antiviral drugs recommended for treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza for the 2023-2024 season are listed in Table 2. Updated information on influenza activity and antiviral resistance is available from the CDC at www.cdc.gov/flu.

TREATMENT RECOMMENDATIONS — Antiviral treatment is recommended as soon as possible for any patient with suspected or confirmed influenza who is hospitalized, has severe, complicated, or progressive illness, or is at increased risk for complications, even if it is started >48 hours after illness onset.1-3 False-negative results can occur with influenza tests; patients in the above groups should receive antiviral treatment despite a negative test, especially when influenza viruses are known to be circulating in the community.4

Antiviral treatment can be considered for otherwise healthy symptomatic outpatients with suspected or confirmed influenza who are not at increased risk for influenza complications if it can be started within 48 hours after illness onset.

TREATMENT — A neuraminidase inhibitor (oral oseltamivir, IV peramivir, or inhaled zanamivir) or the oral cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir marboxil is recommended for treatment of suspected or confirmed uncomplicated influenza in nonpregnant outpatients this season. All of these drugs are active against influenza A and B viruses.

Oseltamivir is preferred for pregnant women, hospitalized patients, and outpatients with severe, complicated, or progressive illness.1

Effectiveness – Use of a neuraminidase inhibitor or baloxavir for treatment of acute uncomplicated influenza in adults shortens the duration of symptoms by about one day.5-8 Although most controlled trials of antiviral drugs have not been powered to assess their efficacy in preventing serious influenza complications, experts have generally interpreted the combined results of controlled trials, observational studies, and meta-analyses as showing that early antiviral treatment of influenza in high-risk and hospitalized patients can reduce the risk of complications.5,9-12

In a meta-analysis of 26 randomized, placebo-controlled trials that included 11,897 healthy children and adults with influenza-like illness, zanamivir was associated with the shortest time to alleviation of influenza symptoms and baloxavir was associated with the lowest risk of influenza-related complications.13

In a randomized, double-blind trial (CAPSTONE-2) in 2184 outpatients ≥12 years old with uncomplicated influenza who were at high risk of developing complications, the median time to symptom improvement was similar with a single dose of baloxavir or 5 days' treatment with oseltamivir (both started within 48 hours after illness onset) in the overall population and in those infected with influenza A(H3N2), but was statistically significantly shorter with baloxavir in those infected with influenza B (median difference 27.1 hours). Use of either drug was associated with a lower incidence of influenza-related complications and fewer antibiotic prescriptions compared to placebo.8

In one meta-analysis of 15 randomized trials that included 6295 outpatient adolescents and adults with influenza, use of oseltamivir did not reduce the risk of hospitalization in the overall population or in those ≥65 years old compared to placebo or standard of care.48

In a randomized, double-blind trial (miniSTONE-2) in 173 otherwise healthy children 1-11 years old with influenza, the median time to alleviation of symptoms was similar with a single dose of baloxavir or 5 days' treatment with oseltamivir (138 vs 150 hours; both started within 48 hours after illness onset).14

A meta-analysis of 5 randomized trials in children with influenza found that starting oseltamivir within 48 hours after illness onset reduced illness duration by about 18 hours (by about 30 hours when trials that enrolled children with asthma were excluded) and decreased the risk of otitis media.15

In a retrospective cohort study in 542 hospitalized adults, oral oseltamivir and IV peramivir were similarly effective in time to defervescence, duration of hospital and intensive care unit stay, and mortality.16 In children hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza, antiviral treatment started within 48 hours after illness onset was associated with shorter durations of hospitalization compared to no antiviral treatment.17

In a randomized, double-blind trial (FLAGSTONE) in 366 patients ≥12 years old hospitalized with severe influenza, the median time to clinical improvement was not statistically significantly different with a combination of a neuraminidase inhibitor (primarily oseltamivir) and baloxavir compared to a neuraminidase inhibitor alone (95.5 vs 100.2 hours).18

Timing – Neuraminidase inhibitors are most effective when started within 48 hours after illness onset, but the results of some observational studies in hospitalized and critically ill patients suggest that treatment started as late as 4-5 days after illness onset can shorten the duration of hospitalization and reduce the risk of complications such as pneumonia, respiratory failure, and death.11,19-21 No data are available on the efficacy of baloxavir treatment that is started >48 hours after illness onset.

Guidelines for treatment of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) recommend antiviral treatment for patients who test positive for influenza regardless of the duration of illness before diagnosis.22

CHEMOPROPHYLAXIS — Oseltamivir, zanamivir, and baloxavir are FDA-approved for chemoprophylaxis of influenza. Post-exposure prophylaxis should be considered within 48 hours of exposure for persons at increased risk of complications who have not received an annual influenza vaccine for the current season, received one within the previous 2 weeks, or might not respond to vaccination, or when the match between the vaccine and circulating strains is poor. It is not recommended for healthy persons exposed to influenza or when >48 hours have elapsed since exposure.

Antiviral chemoprophylaxis with oral oseltamivir or inhaled zanamivir is recommended by the CDC for control of institutional influenza outbreaks.1

Effectiveness – Neuraminidase inhibitors have generally been about 70-90% effective in preventing influenza caused by susceptible strains of influenza A or B viruses.1 In a randomized, double-blind trial in 752 household contacts of patients with influenza, a single dose of baloxavir was 86% effective in preventing clinical influenza in household contacts.23

Timing – When indicated, chemoprophylaxis with oseltamivir or zanamivir should be started no later than 48 hours after exposure and continued for 7 days after the last known exposure. A single dose of baloxavir within 48 hours after exposure is also an option.

For institutional influenza outbreaks, the CDC recommends chemoprophylaxis with oral oseltamivir or inhaled zanamivir for at least 2 weeks; prophylaxis should be continued for up to 1 week after the end of the outbreak.

View the Comparison Chart: Antiviral Drugs for Influenza for 2023-2024

PREGNANCY AND LACTATION — Pregnant women are at increased risk for severe complications of influenza. Oseltamivir and zanamivir appear to be safe for use during pregnancy.24,25 Prompt treatment with oseltamivir is recommended for women with suspected or confirmed influenza who are pregnant or ≤2 weeks postpartum.26-28 Oseltamivir is preferred for treatment of women who are breastfeeding. No data are available on the use of baloxavir in pregnant or breastfeeding women.

Antiviral chemoprophylaxis can be considered for pregnant women who have had close contact with someone suspected or confirmed to have influenza. Zanamivir may be preferred because of its limited systemic absorption, but oseltamivir is a reasonable alternative, especially in women at increased risk for respiratory problems.

RESISTANCE — Over 99% of the recently circulating influenza virus strains tested by the World Health Organization (WHO) have been susceptible to neuraminidase inhibitors.29 Reduced susceptibility of some influenza virus strains, particularly influenza A(H1N1) viruses, to oseltamivir or peramivir can emerge during or after treatment, especially in young children and immunocompromised patients with prolonged viral shedding.30-35 Resistant isolates have usually remained susceptible to zanamivir, but reduced susceptibility to zanamivir has been reported.36 In immunocompromised patients, a double dose of oseltamivir reduced the incidence of oseltamivir resistance compared to standard dosing, but it did not improve efficacy and caused more adverse effects.37

Amino acid substitutions associated with reduced susceptibility to baloxavir have occurred following treatment with a single dose of the drug.7,38 Reduced susceptibility to baloxavir appears to be more frequent in persons infected with influenza A(H3N2) and A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses, particularly children.39,40 Baloxavir monotherapy is not recommended for severely immunocompromised patients because of concerns that prolonged viral replication in such patients could lead to emergence of resistance. Oseltamivir and peramivir may be active against influenza virus strains with reduced susceptibility to baloxavir.41 Baloxavir is active against neuraminidase inhibitor-resistant strains of influenza A and B viruses, including A(H1N1), A(H5N1), A(H3N2), and A(H7N9).

The adamantanes amantadine and rimantadine are active against influenza A viruses, but not influenza B viruses. As in recent past seasons, resistance to these drugs is high (>99%) among circulating influenza A(H3N2) and A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses; neither amantadine nor rimantadine is recommended for treatment or chemoprophylaxis of influenza.

ADVERSE EFFECTS — Nausea, vomiting, and headache are the most common adverse effects of oseltamivir; taking the drug with food may minimize GI adverse effects. Oseltamivir has been associated with bradycardia in critically ill patients.42 Diarrhea, nausea, sinusitis, fever, and arthralgia have been reported with zanamivir. Inhalation of zanamivir can cause bronchospasm; the drug should not be used in patients with underlying airway disease. Diarrhea and neutropenia have occurred with peramivir.43

Baloxavir appears to cause less nausea and vomiting than oseltamivir.44

Neuropsychiatric events, including self-injury and delirium, have been reported in patients taking neuraminidase inhibitors or baloxavir, but a causal relationship has not been established, and neuropsychiatric dysfunction can be a complication of influenza itself.45 Hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis, have been reported with all of these drugs.

USE WITH THE LIVE-ATTENUATED VACCINE — Use of oseltamivir or zanamivir within 48 hours before, peramivir within 5 days before, or baloxavir within 17 days before administration of the live-attenuated intranasal influenza vaccine (FluMist Quadrivalent) could inhibit replication of the vaccine virus, reducing the vaccine's effectiveness, and is not recommended.46 Persons who receive any of these antiviral drugs during these specified times and through 2 weeks after receiving the live-attenuated vaccine should be revaccinated with an inactivated or recombinant age-appropriate influenza vaccine.47

DRUG INTERACTIONS — Coadministration of dairy products, beverages, antacids, laxatives, multivitamins, or other products containing polyvalent cations (e.g., calcium, aluminum, iron, magnesium, selenium, zinc) can reduce serum concentrations of baloxavir and should be avoided.

- CDC. Influenza antiviral medications: summary for clinicians. September 27, 2023. Available at: https://bit.ly/3pY5ixT. Accessed October 26, 2023.

- TM Uyeki et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America: 2018 update on diagnosis, treatment, chemoprophylaxis, and institutional outbreak management of seasonal influenza. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68:895. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy874

- Committee on Infectious Diseases. Recommendations for prevention and control of influenza in children, 2023-2024. Pediatrics 2023; 152:e2023063773. doi:10.1542/peds.2023-063773

- CDC. Information for clinicians on influenza virus testing. August 29, 2022. Available at: https://bit.ly/3Q3wrOu. Accessed October 26, 2023.

- CC Butler et al. Oseltamivir plus usual care versus usual care for influenza-like illness in primary care: an open-label, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2020; 395:42. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(19)32982-4

- IDSA. IDSA statement on neuraminidase inhibitors. Available at: http://bit.ly/34AdhEU. Accessed October 26, 2023.

- FG Hayden et al. Baloxavir marboxil for uncomplicated influenza in adults and adolescents. N Engl J Med 2018; 379:913. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1716197

- MG Ison et al. Early treatment with baloxavir marboxil in high-risk adolescent and adult outpatients with uncomplicated influenza (CAPSTONE-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; 20:1204. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30004-9

- In brief: Concerns about oseltamivir (Tamiflu). Med Lett Drugs Ther 2015; 57:14.

- MK Doll et al. Safety and effectiveness of neuraminidase inhibitors for influenza treatment, prophylaxis, and outbreak control: a systematic review of systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017; 72:2990. doi:10.1093/jac/dkx271

- J Katzen et al. Early oseltamivir after hospital admission is associated with shortened hospitalization: a 5-year analysis of oseltamivir timing and clinical outcomes. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 69:52. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy860

- Y Sharma et al. Effectiveness of oseltamivir in reducing 30-day readmissions and mortality among patients with severe seasonal influenza in Australian hospitalized patients. Int J Infect Dis 2021; 104:232. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.01.011

- J-W Liu et al. Comparison of antiviral agents for seasonal influenza outcomes in healthy adults and children: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4:e2119151. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.19151

- J Baker et al. Baloxavir marboxil single-dose treatment in influenza-infected children: a randomized, double-blind, active controlled phase 3 safety and efficacy trial (miniSTONE-2). Pediatr Infect Dis J 2020; 39:700. doi:10.1097/inf.0000000000002747

- RE Malosh et al. Efficacy and safety of oseltamivir in children: systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66:1492. doi:10.1093/cid/cix1040

- JS Lee et al. Clinical effectiveness of intravenous peramivir versus oseltamivir for the treatment of influenza in hospitalized patients. Infect Drug Resist 2020; 13:1479. doi:10.2147/idr.s247421

- AP Campbell et al. Influenza antiviral treatment and length of stay. Pediatrics 2021; 148:e2021050417. doi:10.1542/peds.2021-050417

- D Kumar et al. Combining baloxavir marboxil with standard-of-care neuraminidase inhibitor in patients hospitalized with severe influenza (FLAGSTONE): a randomised, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled, superiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2022; 22:718. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(21)00469-2

- JK Louie et al. Neuraminidase inhibitors for critically ill children with influenza. Pediatrics 2013; 132:e1539. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-2149

- SG Muthuri et al. Effectiveness of neuraminidase inhibitors in reducing mortality in patients admitted to hospital with influenza A H1N1pdm09 virus infection: a meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet Respir Med 2014; 2:395. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(14)70041-4

- JK Louie et al. Treatment with neuraminidase inhibitors for critically ill patients with influenza A (H1N1)pdm09. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:1198. doi:10.1093/cid/cis636

- JP Metlay et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 200:e45. doi:10.1164/rccm.201908-1581st

- H Ikematsu et al. Baloxavir marboxil for prophylaxis against influenza in household contacts. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:309. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1915341

- EJ Chow et al. Clinical effectiveness and safety of antivirals for influenza in pregnancy. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021; 8:ofab138. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab138

- V Ehrenstein et al. Oseltamivir in pregnancy and birth outcomes. BMC Infect Dis 2018; 18:519. doi:10.1186/s12879-018-3423-z

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 753: assessment and treatment of pregnant women with suspected or confirmed influenza. Obstet Gynecol 2018; 132:e169. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000002872

- IK Oboho et al. Benefit of early initiation of influenza antiviral treatment to pregnant women hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza. J Infect Dis 2016; 214:507. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiw033

- CDC. Recommendations for obstetric health care providers related to use of antiviral medications in the treatment and prevention of influenza. September 15, 2022. Available at: https://bit.ly/35nzZlN. Accessed October 26, 2023.

- EA Govorkova et al. Global update on the susceptibilities of human influenza viruses to neuraminidase inhibitors and the cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir, 2018-2020. Antiviral Res 2022; 200:105281. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2022.105281

- AC Hurt et al. Characteristics of a widespread community cluster of H275Y oseltamivir-resistant A(H1N1)pdm09 influenza in Australia. J Infect Dis 2012; 206:148. doi:10.1093/infdis/jis337

- C Renaud et al. H275Y mutant pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus in immunocompromised patients. Emerg Infect Dis 2011; 17:653. doi:10.3201/eid1704.101429

- JW Tang et al. Transmitted and acquired oseltamivir resistance during the 2018-2019 influenza season. J Infect 2019; 79:612. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2019.10.020

- R Roosenhoff et al. Viral kinetics and resistance development in children treated with neuraminidase inhibitors: the Influenza Resistance Information Study (IRIS). Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71:1186. doi:10.1093/cid/ciz939

- B Lina et al. Five years of monitoring for the emergence of oseltamivir resistance in patients with influenza A infections in the Influenza Resistance Information Study. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2018; 12:267. doi:10.1111/irv.12534

- E Takashita et al. Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus exhibiting enhanced cross-resistance to oseltamivir and peramivir due to a dual H275Y/G147R substitution, Japan, March 2016. Euro Surveill 2016; 21:30258. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.es.2016.21.24.30258

- R Trebbien et al. Development of oseltamivir and zanamivir resistance in influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus, Denmark, 2014. Euro Surveill 2017; 22:30445. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.es.2017.22.3.30445

- E Mitha et al. Safety, resistance, and efficacy results from a phase IIIb study of conventional- and double-dose oseltamivir regimens for treatment of influenza in immunocompromised patients. Infect Dis Ther 2019; 8:613. doi:10.1007/s40121-019-00271-8

- T Uehara et al. Treatment-emergent influenza variant viruses with reduced baloxavir susceptibility: impact on clinical and virologic outcomes in uncomplicated influenza. J Infect Dis 2020; 221:346. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiz24

- E Takashita et al. Influenza A(H3N2) virus exhibiting reduced susceptibility to baloxavir due to a polymerase acidic subunit I38T substitution detected from a hospitalised child without prior baloxavir treatment, Japan, January 2019. Euro Surveill 2019; 24:1900170. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.es.2019.24.12.1900170

- E Takashita et al. Human-to-human transmission of influenza A(H3N2) virus with reduced susceptibility to baloxavir, Japan, February 2019. Emerg Infect Dis 2019; 25:2108. doi:10.3201/eid2511.190757

- M Seki et al. Adult influenza A (H3N2) with reduced susceptibility to baloxavir or peramivir cured after switching anti-influenza agents. IDCases 2019; 18:e00650. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2019.e00650

- R MacLaren et al. Oseltamivir-associated bradycardia in critically ill patients. Ann Pharmacother 2021; 55:1318. doi:10.1177/1060028020988919

- Peramivir (Rapivab): an IV neuraminidase inhibitor for treatment of influenza. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2015; 57:17.

- Baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza) for treatment of influenza. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2018; 60:193.

- S Toovey et al. Post-marketing assessment of neuropsychiatric adverse events in influenza patients treated with oseltamivir: an updated review. Adv Ther 2012; 29:826. doi:10.1007/s12325-012-0050-8

- Influenza vaccine for 2023-2024. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2023; 65:161.

- LA Grohskopf et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices – United States, 2023-24 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep 2023; 72:1. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr7202a1

- R Hanula et al. Evaluation of oseltamivir used to prevent hospitalization in outpatients with influenza: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2023 June 12 (epub). doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.0699